Cognitive Load and UI Design: Designing for the Brain, Not Just the Eye

Modern UI design has never been just about aesthetics—it's about psychology. Learn how cognitive science principles like Hick's Law and the Serial Position Effect can guide smarter interface decisions.

2024-12-15

Modern UI design has never been just about aesthetics—it's about psychology. In this post, we'll explore how cognitive science principles like Hick's Law and the Serial Position Effect can guide smarter interface decisions. You'll learn how to reduce friction, improve decision-making speed, and create interfaces that feel intuitive because they're built for how users actually think.

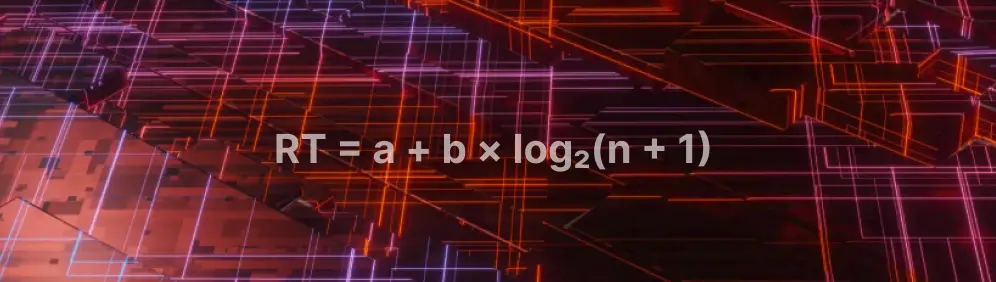

Hick's Law: Decision Time and Interface Complexity

Hick's Law states that the time it takes for a person to make a decision increases logarithmically with the number of choices presented. In UI design, this principle is a powerful argument for simplicity. When users are confronted with too many options—be it navigation links, form fields, or filter settings—their cognitive load spikes, leading to hesitation or abandonment. A well-designed interface minimizes decision points or groups them logically, allowing users to process choices faster and more confidently. Think of how Google's homepage offers a single search bar: it's not just minimalist, it's cognitively optimized.

Advanced applications of Hick's Law go beyond reducing options—they involve designing choice architecture. For example, progressive disclosure hides complexity until it's needed, while predictive UI elements (like autocomplete or smart defaults) reduce the mental effort required to make a choice. In enterprise dashboards or e-commerce platforms, where complexity is unavoidable, designers can use visual hierarchy, chunking, and contextual cues to guide users through decisions without overwhelming them. Hick's Law isn't about dumbing down interfaces—it's about designing for how humans actually process information.

Example: Progressive Disclosure in a Settings Panel

<!-- Initial simplified UI -->

<button onclick="toggleAdvanced()">Show Advanced Settings</button>

<div id="advanced-settings" style="display: none;">

<label>

<input type="checkbox" /> Enable experimental features

</label>

<label>

<input type="checkbox" /> Use legacy rendering engine

</label>

</div>

<script>

function toggleAdvanced() {

const panel = document.getElementById('advanced-settings');

panel.style.display = panel.style.display === 'none' ? 'block' : 'none';

}

</script>

Why it works: Instead of overwhelming users with all options at once, this pattern reveals complexity only when needed—reducing cognitive load and aligning with Hick's Law.

Fitts's Law: Speed, Accuracy, and Target Size

Fitts's Law predicts that the time to move to a target area (like a button or link) is a function of the distance to and size of the target. In UI terms, this means that larger, closer buttons are faster and easier to click or tap. It's why mobile interfaces prioritize thumb-friendly zones and why call-to-action buttons are often oversized and centrally placed. But Fitts's Law also applies to subtle design decisions: dropdown arrows, close icons, and hover targets all benefit from being generously sized and well-positioned. Ignoring this law can lead to frustrating interactions, especially on touch devices or for users with motor impairments.

Example: Large, Clickable CTA Button

<style>

.cta-button {

padding: 16px 32px;

font-size: 1.2rem;

background-color: #0078d4;

color: white;

border: none;

border-radius: 8px;

cursor: pointer;

transition: background-color 0.2s ease;

}

.cta-button:hover {

background-color: #005ea2;

}

</style>

<button class="cta-button">Start Free Trial</button>

Why it works: The button is large, visually distinct, and easy to click—especially on mobile. This reduces movement time and error, directly applying Fitts's Law.

Serial Position Effect: Memory and UI Flow

The Serial Position Effect, rooted in cognitive psychology, reveals that people are more likely to remember items at the beginning (primacy) and end (recency) of a sequence. In UI design, this has profound implications for how we order navigation menus, onboarding steps, or product listings. Placing key actions or information at the start and end of a flow increases the likelihood that users will notice and retain them. For instance, in a multi-step form, the first and last fields should be the most critical or engaging—users are more likely to complete them accurately and remember their content.

Designers can also use this effect to influence user behavior. In e-commerce, placing high-margin or popular products at the top and bottom of a list can subtly guide purchasing decisions. In onboarding flows, starting with a compelling value proposition and ending with a clear next step reinforces engagement. The Serial Position Effect reminds us that UI isn't just about layout—it's about sequencing, memory, and psychological impact. When used intentionally, it transforms passive interfaces into persuasive experiences.

Reducing Decision Complexity

A progress bar simplifies the user's mental model of the task. Instead of facing an ambiguous or overwhelming form, users see a clear path with defined steps. This reduces cognitive load by breaking a complex decision (completing a form) into manageable chunks. It helps users feel in control, which speeds up decision-making — exactly what Hick's Law predicts.

Anchoring Memory and Motivation

Progress bars also tap into the Serial Position Effect by reinforcing the beginning and end of a sequence. The first step sets expectations (primacy), and the final step often includes a satisfying "Finish" or "Submit" action (recency). Visually tracking progress motivates users to continue, especially as they approach the end — a psychological nudge that improves completion rates.

Example: Ordered Navigation Menu

<nav>

<ul>

<li><a href="/dashboard">Dashboard</a></li> <!-- Primacy -->

<li><a href="/projects">Projects</a></li>

<li><a href="/reports">Reports</a></li>

<li><a href="/settings">Settings</a></li>

<li><a href="/logout">Log Out</a></li> <!-- Recency -->

</ul>

</nav>

Why it works: Users are more likely to remember and interact with the first and last items. Placing high-priority actions like "Dashboard" and "Log Out" in those positions leverages the Serial Position Effect.

Conclusion: Designing with Cognitive Empathy

User interfaces aren't just visual artifacts—they're cognitive environments. By grounding design decisions in principles like Hick's Law, Fitts's Law, and the Serial Position Effect, we move beyond aesthetics and into the realm of psychological precision. These laws remind us that every pixel, every interaction, and every sequence carries cognitive weight. When we reduce decision complexity, optimize for motor behavior, and align with memory patterns, we create interfaces that feel effortless—not because they're simple, but because they're intuitively human.

Designing for the brain means designing for clarity, confidence, and momentum. Whether it's a progress bar that guides users through a form, a button that invites action with ease, or a menu that subtly nudges memory, the best interfaces don't just look good—they think well.